The Ethics of Debt

Feb 21, 2016According to a report from the Jubilee Debt Campaign, there are currently 24 countries facing a full-blown debt crisis, with 14 more on the verge.

International Debt, the debts that nations, often quite poor, owe to other nations and banks, is leading to disaster. There is something like 200 trillion dollars worth of such debt, and 24 nations in crisis because they can’t pay off their debts. The burden of debt falls on the poor and disenfranchised, as debtor nations impose taxes and cut back benefits. We’re talking massive human tragedy unfolding around the world.

Debt seems a very useful institution, and if usurious practices are under control, basically just. You have a debtor, who borrows money and promises to repay it with interest. You have a creditor, who loans the money, and expects to get repaid with interest. As long as everyone is a reasonably rational agent --- no children or crazy people involved --- it seems a straightforward, fair, and extremely useful human institution. It allowed me to buy a house; it allows students from backwards countries like America to get a college education.

But this model doesn’t scale up to cases in which nations and other institutions are the lenders and borrowers. The model assumes that the same agent takes out the loan and then later has to repay it or incur the consequences. That’s a key part of the fairness of the institution of debt∂. But that’s not what happens when countries take out loans.

These debts can last for a long time. One group of leaders may negotiate the loan, and use the money to make themselves popular, by using the money to provide benefits to their constituents. Another group is faced with paying it off, years or even generations later, by taxing and reducing benefits for another group of constituents.

We can call the nation “agent” doesn’t change the facts. Loans are negotiated by people, and it’s people that have make the painful decision to repay them or not. That’s where the real agency lies, whatever we call “the agent. And there is a difference between expecting to repay a loan yourself, and expecting someone down the line, who happens to be a part of the same institution or nation as you are, to pay it.

When people make decisions to lend or borrow on behalf of institutions, you get two sets of costs and benefits --- on both sides of the deal. A bank’s agent may get short term benefits for being the one who negotiates the loan, independently of whether in the longer term the loan gets paid off.

The model of a just loan agreement will work if everyone acts rationally relative to the costs and benefits to the whole group to institution represents, rather than their own. But that doesn’t always happen. It didn’t happen on Wall Street. Big banks made it advantageous to their broker to make risky gambles, which then came back to haunt the banks --- at least until we taxpayers bailed them out.

So we need a new model of just loans for nations. That’s above my paygrade to figure out. But listen to the show this week, and maybe Ken and I and our guest, UMass economist Julie Nelson, will come up with a solution.

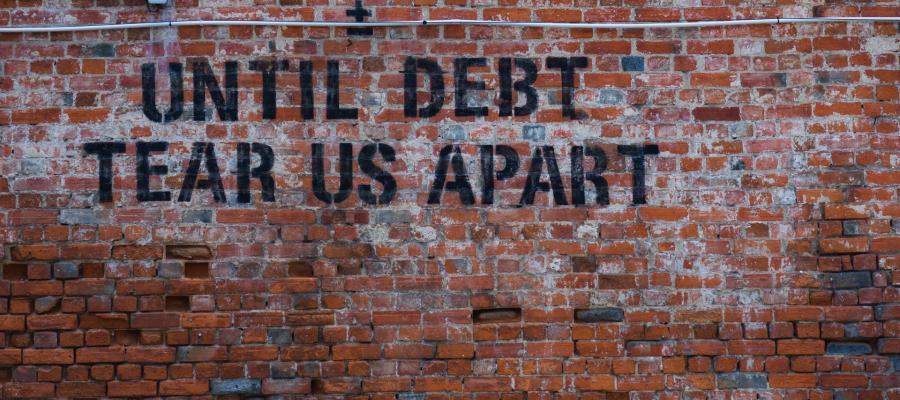

Photo by Timothy Eberly on Unsplash

Comments (4)

Harold G. Neuman

Thursday, February 25, 2016 -- 4:00 PM

Well, I don't want to soundWell, I don't want to sound like some bible-thumping zealot from ultra-conservative middle America, but, to piggy back upon posts regarding religion and finding meaning in a material world, I felt sufficiently affirmed to state the following: Usury is still usury, even when it is sanctioned as business as usual. Any time a practice becomes and remains legal, particularly where the exchange of money is involved, sooner or later someone will abuse the practice and privilege. This is painfully true in banking where the too-big-to-fail maxim perpetuated the economic chaos that struck towards the end of 2008. It is also endemic for insurance of all types which I have formerly characterized as legalized extortion. The propensity of human beings to want to have everything that they can have at any cost is a character flaw which has become epidemic in the illustrious West and is rapidly catching on in other parts of the world. Sad to tell, but all of this supports my notion that, for better or worse, we get pretty much what we deserve, i.e., we both prosper and suffer from the effects of history. Inasmuch as we have put ourselves in harms way, trading unfettered prosperity for cautious stability and long-term sustainability, the djinn is out of the bottle and we have no mechanism through which we might put him back. If Keynes is not tossing in his grave, he damned well should be.

Neuman.

Gary M Washburn

Friday, February 26, 2016 -- 4:00 PM

Let's not get into "moralLet's not get into "moral hazard"! It's a one-sided and devious "principle". Most private loans are secured by collateral or some insurance plan anyway, so the lender is just being perverse in pressing that damn point. But I think the topic is public borrowing. Think Greece or Nauru, not credit-card debt. Greeks and Romans despised usury because they assumed money was stable and believed lending would destroy nobles and elevate the 'ignoble' into their position in society. It also smacked of the power to tax, which any government is rightly jealous of. But that is the real issue, isn't it? Doesn't predatory lending assert a kind of sovereignty, not only demanding repayment, but control over public policy? During the Cold War there was a lot of lending to corrupt regimes who promised to oppose the other side. Today most of these countries are coming to their senses, though some exceptions may be notable. But the problem today is more a matter of lenders insinuating themselves into decisions that are properly the prerogative of the people of the borrowing nation, and their leaders, not the bankers they owe money to. Speaking to the philosophy of it, the quantification of value is a contradiction in terms.

Pedestrian

Sunday, April 3, 2016 -- 5:00 PM

Actually I have to agree withActually I have to agree with our modern financial philosophers, without debt...there is no money. Debt within the micro economic sphere is most often a tool and short term, i.e., it's paid off. However, debt at the macroeconomic level partially defines moral hazard. It is patently immoral for a country's leaders to borrow money and put generations of his country's population often into perpetual debt. In fact, debt has become the chains that binds us all, as far too many economies have become cost-of-capital sensitive, leading [its] performance to become directly proportional to and dependent upon, a customer's ability to borrow the money.The debt crisis will lead to continued world recession and if not reduced...world depression.

Harold G. Neuman

Sunday, October 14, 2018 -- 12:47 PM

Apparently, the world was notApparently, the world was not facing up to its debt crisis in 2016 (presumably, said debt crisis remains and is still a crisis---unless someone has found a solution and has not bothered to tell anyone). On the other hand, other things equal (see: John Rawls), can it be that, inasmuch as most of the world is in debt, there really is no crisis at all? What WOULD it mean if the entire world debt were never repaid? Would the world become one gigantic Lehman Brothers-style bankruptcy? Or, worse(?), would we have world war of some kind or other? I attained little background in economics while in school, so cannot fathom the debt thing on a world scale. Do any Economists KNOW what this means, or are they just playing with smoke and mirrors? Just asking...