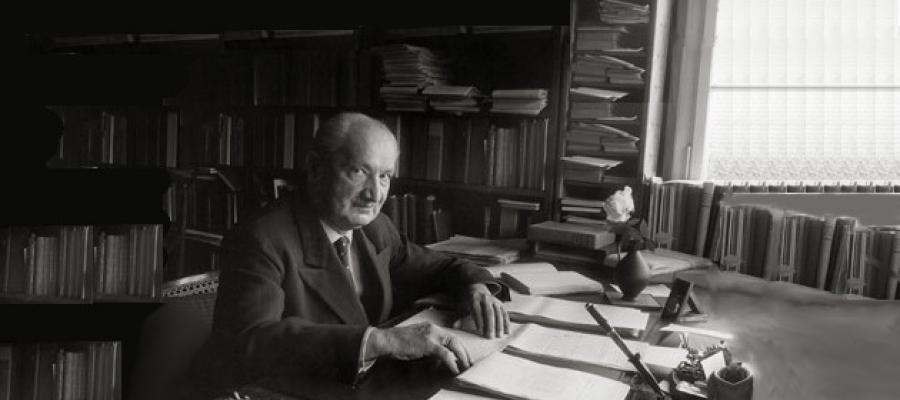

Heidegger

Jun 28, 2015Best known for his work Being and Time, Martin Heidegger has been hailed by many as the greatest philosopher of the twentieth century.

Martin Heidegger is the Continental philosopher most analytic philosophers love to hate. I actually never knew enough about Heidegger to form much of an opinion. I knew that he said that “Nothings noths” (Das Nichts nichtet), giving Carnap a paradigm of meaningless, unverifiable, unfalsifiable, metaphysical gibberish. I knew that he invented the term “Dasein” – “Being There”, for human beings, or human existence, or something like that, and it sounded profound. And over the years I met many thoughtful philosophers who thought highly of his ideas, like Burt Dreyfus, Mark Wrathall, and Tom Sheehan. But my attempts to read Heidegger were few, far between, and frustrating.

Recently one of these thoughtful philosophers, Kevin Gin, a graduate student at UC Riverside, a student of Wrathall’s, convinced me to take another look. He sees a connection between some of my ideas, about unarticulated constituents and self-knowledge, and various thoughts of Heidegger. So maybe the guy is profound, after all! With Kevin’s help, I’m getting a bit of a sense of some of what Heidegger was doing, and find it interesting.

As for Dasein, Rocks aren’t Daseins (or Daseine? My German is rusty, to put it charitably). Lizards aren’t, but they come closer than rocks. And at least most other animals aren’t. But we are.

I think the terminology is supposed to get at how Heidegger conceives of human beings. Daseins contrast with a Cartesian egos. The Cartesian ego is basically a thinker and an observer, who reasons from its existence and its ideas, to God’s existence, and hence to the world and other people. The starting point in this immaterial ego with its ideas; the struggle is to justify belief in the rest of the world.

With Dasein, as I get it, it kind of goes the other way. Considering myself as Dasein, I am not basically a thinker and an observer, but an agent, a do-er immersed in the world from the getgo. And things in the world aren’t basically presented to me as what my ideas might or might not stand for, but as tools I have to use for various purposes. The Cartesian picture, seeing myself as a separate entity, a mind, the world as something quite separate, and my ideas as linking the two by the relation of representation is, insofar as it makes sense, is the result of an intellectual struggle, recapitulated in a more reflective way in philosophy, not the starting point for human cognition or philosophical thinking.

Rocks simply persist through time. Animals, and plants too, for that matter, react to circumstances, in order to survive and reproduce. But humans lead lives, forming projects --- goals --- and making choices about how to achieve them. And our world, or worlds, arise out of this.

Put this way, Heidegger sounds sort of naturalistic --- that is, a philosopher who wants to understand consciousness, thought, freedom and the like in the natural world as natural processes, based in evolution It seems to me that, in pursuing his project, Heidegger’s was led to some of the same insights about representation and thought as philosophers like Dretske, Dennett or Millikan, insights that, IMHO, I’m getting at too. But we explicitly see humans as basically biological beings, with capacities for handling information developed by evolution. Heidegger never says anything like that, as far as I know.

To move on to a different issue about Heidegger, should we be comfortable in finding good ideas in someone who was a member of the Nazi party?

Well, I suppose, good ideas are where you find them. All I really know is that Heidegger joined the Nazi party in the early thirties, probably as a condition for becoming rector of Freiburg. He gave up that job a couple of years later. In the meantime, he dutifully implemented some Nazi policies at Freiburg. People disagree on whether he was an enthusiastic Nazi or a reluctant and somewhat opportunistic dupe. He never tells us much. Apparently in his diaries, the “Black Books”, Heidegger linked anti-Semitic ideas with themes in his philosophy, even before joining the Nazi Party. But he dedicates his major work, Sein und Seit, to Husserl, and he had an affair with his pre-war student Hannah Arendt, both Jews. Ambivalence? Duplicity? Deprativity? All I know is that if he read Mein Kampf before joining the Nazi Party, I’d have to see him as more than merely naïve (Arendt’s defense of him, after World War II, when she helped get him the right to teach again). Shuka Kalantari will tell us a bit about this is her report, and I’m sure Thomas Sheehan, our guest, will shed some light on it.

Final deep thought:

Now that I know I am but Dasein

I’m thinking things will turn out fine

First I’ll be something,

And then I’ll be nothing

And noth away til the end of time

Comments (15)

Gary M Washburn

Friday, June 26, 2015 -- 5:00 PM

Dasein is that entity forDasein is that entity for which its being is the issue. Rocks don't. I am not a great fan of Heidegger, but at his best he is brilliant. At his worst he is repetitive, haughty, and (strangely) a suck-up to whatever power structure he thinks can advance his career. But give credit where it's due.

When I asked my instructor what "ownmost" means, I was told, "crowded". Interesting answer. It is, of course, analytically empty. But that is only an issue to those so dogmatically committed to analysis they fail to see the crashing of the reductive process as the only real induction reason can achieve. And so they cease the process long before it can come to that abysmal end. This is why logicians, or analytical philosophers, never consider arguments of more than a few sentences, for the formalism results in a deformation so complete that semantics is retroactively altered throughout all that can be reasoned. Now, even Heidegger did not confront the temporality of this regression forthrightly, but opted, as all before and most since have done, for a dogmatic transcendence. As if permanence were the "essence" of time. But until we place language firmly in the hands of its true creators, weak, emotional persons, we won't see much meaning in the contrast between dogmas.

focus8@telus.net

Friday, June 26, 2015 -- 5:00 PM

For my money Ken Wilber isFor my money Ken Wilber is the greatest philosopher of the 20th century and perhaps of this one, too. I would very much like for John and Ken to invite him onto the program some day soon.

Submitted by C. Marxer, June 27, 2015

Gary M Washburn

Saturday, June 27, 2015 -- 5:00 PM

Some AQAL! Sounds likeSome AQAL! Sounds like "turtles all the way down" to me. What 'Wilbur' has to do with Heidegger is beyond me.

Heidegger asks: "What does being mean?" Analytical thinkers don't dare do so because their whole system collapses from any uncertainty about it. That's why "Anglo-American philosophy" is dogmatics through and through. Not to say that Heidegger was much use in expressing the meaning even of the question, let alone in pursuing it. Any pretensions he once had of grappling with the question without prejudice is long since proved a fraud. But this does not belittle the question itself. Analysis cannot supply itself with its terms, and must take the form of reasoning as its mission. It is evangelical in this sense. Preaching, not thinking. Heidegger, however, was in the long run no better. Being and time is his obeisance to his teacher, and superior, in which he characterizes human existence as epochal. The problem, of course, is that Husserl regarded the epochal structure of time as impersonal, even dogmatically depersonalized. And so Husserl dismissed Heidegger's magnus-opus as "psychologism". But Husserl was already being pressured out by the Nazis, leaving Heiddeger free to seek Nazi approval by proclaiming a mystical connection with ancient wisdom. If wisdom it be.

However, the question remains. How does meaning arise? Either as the meaning that humans aspire to, or the more technical issue of the meaning of terms in any language and language per-se. The "linguistic" tradition pretends to make this its motivating issue, but is so convicted in the "entail" of reason or logic that this pretense is ludicrous. As if freedom were an "entail"! The reason reason does not manage to encompass reality is not that reality is somehow remiss in its failing to obey the rules of logic or, supposed, causality, or because reason lacks facts. It is because reason cannot supply its own terms. There has to be freedom if there is to be any concrete necessity. That is, freedom is the more encompassing term. What eludes the entail nourishes the growth of meaning, supplying the terms of that entail. Some say time is one. What a joke! Time is no one, for the supply of meaning is never the possession or enclosure of any epochal structure. This explains why the three threads of Western philosophy have all fallen flat, the Anglo-American, the Continental, and the Existential. That is, all of them would reduce value to the quantifier. The only result of that count is the loss of the enumerator in it.

Next:

The psychology of mood.

Gary M Washburn

Sunday, June 28, 2015 -- 5:00 PM

Heineken? Actually, HeideggerHeineken? Actually, Heidegger was a wine drinker.

The Stambaugh translation is a much more readable version of Being and Time than the Harper and Rowe edition. Kaelin provides a refreshingly lucid evaluation of it. After Husserl was rendered unnecessary to his career, Heidegger reevaluated his whole methodology in what he called the "kehre", or "turn" (literally, a fork in the road). The result is a tumult of shoddy reading of ancient thinkers and a number of revisions to the idea (and spelling) of "being". It's all a clumsy mess at bottom, but since no one else even tried to broach the subject he should at least be noted for this. It's appalling to see how ignorant American "philosophers" are of philosophy! Husserl was thought in his day to be the living spirit of German philosophy, inheritor of the legacies of Kant and Hegel. Heidegger was his heir apparent, and even though he betrayed that trust, he did become an essential influence for the existentialist movement that came after him, though Sartre was actually influenced more by Husserl directly (few read his earliest works on imagination, the direct implication of Husserl's "intentional object").

In Being and Time, Heidegger notes a lack of understanding of human moods, seeming to recommend the work be taken up. Considering his time, I suppose he must have intended a sort of Freudian analysis. But I took up the challenge in my own terms, seeing in it a chance to explain the role of reason in emotions, which is coterminous, and not one subjected to the other. This, because being is an unresolved issue, and the pursuit of certitude and persistence in the categories and terms of existence is corrupted as a result. The consequence is that a rigorous effort to sustain them invariable entails change. But since the very crux of the conceit of enduring time is that change is intolerable or a corruption of the conceit of a perfected and permanent "being", that change cannot be permitted to be recognized. And so it can only take the form of an alteration in the character of that conceit. We "know" the consequent term cannot outstrip its antecedent (for this would implicate our determinacy and even our identification of it) nor can the effect be the agent of its cause (for this would confuse the order of "being" as we suppose we know it). And so we alter in the sense or character of our thoughts, in an emotional variation of how sure we are of them or how we feel about them. This seems impertinent to the formal fact. But if the extremity of rigor is that we are lost that conceit, if only in the least term of it, that "being" is a perfect or permanent term upon which the quantifier (to which "being" is the qualifier) can be relied upon to preserve the "law of contradiction" even in a real temporal world, then that quantifier is lost and quality, the meaning and worth of time, is the only real issue. and so feelings precede reason as a posterior entailment. We cannot anticipate the worth of time, or the meaning of being. And so no resoluteness can be "authentic".

MJA

Wednesday, July 1, 2015 -- 5:00 PM

A Simple Thought:A Simple Thought:

I've connected everything in the Universe

Finding One or all just the same

So nothing is truly something

And something simply is.

= is

MJA

Wednesday, July 1, 2015 -- 5:00 PM

Being:Being:

B?

And if A = B, and B = C, then A = C

But what about B?

They all look different to me, so what is truth,

What can it B?

Different or equal?

What should it B?

To B or not to B?

That is the question.

The Nature of B,

Aristotle, Shakespeare and Me.

=

MJA

Gary M Washburn

Wednesday, July 1, 2015 -- 5:00 PM

Humpty-Dumpty?Humpty-Dumpty?

"Twas brillig and the slithy toves did gyre and gimble in the wabe...."

Brad

Friday, July 3, 2015 -- 5:00 PM

I think Perry's contrast ofI think Perry's contrast of the Cartesian ego that is a kind of vanishing point that thinks, and that recovers a world from doubt in reflection, with the Heideggerian being that is there in the world before thinking, is apt.

Gary M Washburn

Monday, July 6, 2015 -- 5:00 PM

Brad,Brad,

Descartes spent his life eluding the censors. Had he asked the real question, how it is we can even state the proposition "cogito sunt", he would have been accused of heresy, since language could only be attributed to the Christian god. Heidegger had the advantage of being influenced by thinkers like Hegel, Simmel, Brentano, Dilthey, and Weber. But to attribute language to a preexisting world is hardly any more satisfying than inventing a divinity as the source of it. And by the time Being and Time was being written it was no great innovation, and it did not impress his mentor Husserl.

Michael,

You are perfectly at liberty to suppose you know what you mean, but not that I do, nor that I am persuaded you do. Discipline can seem constraining, and even imperious in the hands of soneone like Heidegger, infamously a bully to his students. But this is because he, like so many others, do not drive the rigor to its fullest extent in self-criticism. But without a critical response from others we cannot situate even that resolution to the violence of discourse. It is disciplined responsiveness that saves us from being bullies to each other, and repudiating rigor altogether is no less bullying than the rigorous criticism that stops short of self-criticism.

The notion of "anticipatory resoluteness" could have an important place as a call for epistemic discipline, for a responsiveness to evidence of events and meaning not predicted in reason. But Heidegger's undercooked material on "being towards death" rather spoils the effect. The one thing we cannot anticipate is the worth of our being. And, no, it is not for others to take the measure of us. But it is through the responses of others that we do get whatever evidence there may be in life of anything opportune through our being in life of anything worthy of our time. We are not the measure of each other, nor of ourselves. But we are the act which may be opportune of a response through which we can learn and revise what worth there may be in us. But what does "being already in a world" then mean? Heidegger gets a lot of grief for attributing a kind of agency to "being" and "world". But there is a sense in which the world is a kind of agency. The world is its offer of the facile term of our knowing it. Compare the difference between a foreign language and your native tongue and see immediately what I mean. This difference in facile "hearing" is not a simple matter of biology or socialization. It is an intensive engagement in a drama of uncompleted thought and meaning constantly revived and revisited and in the throes of examining ramifying and chancing to act and to respond. With every chance we take we differ, not just the meaning of the terms, but the very context of the drama engaged. This is not a game, as Wittgenstein would have it. It takes up the offer the world is as the means of attenuating the loss and the responsibility that is the ultimate meaning of it. Meaning is a drama of loss, lost conceit that we know what we mean, and the freedom enabled, through that loss, that its response is in responsibility of recognizing its worth, its worth even to the world, as the differing of the context of its lexical and formal tools. But we are never as alone in that drama of act and response than we are as "being already in a world" and so received the facile term attenuated the worth of that act and that response to each other. But there can be no resoluteness in the drama, as there always is in that facile attenuation of loss and responsibility the world is. It is precisely that we not anticipate death that we know the world at all. And so, we are already inauthentic there. But Heidegger does not define his "inauthenticity" as "being in the world", but as irresoluteness in anticipation of death. And yet we cannot know the worth of our being save as the response evidenced how opportune we may be to each other in the examination and measure of that worth. The details are difficult. Much more difficult than any text Heidegger ever produced. But the notion of "anticipatory resoluteness" is a contradiction so glaring as to demonstrate conclusively the same Calvinist dogma Descartes echoes in the notion of the "cogito sunt". That is, the notion, circuitously formulated through a thousand and more years of entrenched power struggles amongst the various intellectual religious and political/military power centers from which, in the form of the Reformation, ultimately emerged as the paradigm of covenant enshrined as the feudal relationship of lord and vassal, abstracted as a personal relation to the Christian god. Substitute "being", and you get the dogmatic character of Heidegger's thought, early and late, before and after the "kehre".

MJA

Tuesday, July 7, 2015 -- 5:00 PM

Hi Gary, I haven't readHi Gary, I haven't read Heidegger so I cannot alas respond to your comments above of which I fail to understand. As for Descates and "cogito sunt" I do understand. Descates rented a room in Ulm where he climbed into a stove to reboot his mind from all the knowledge taught to him that later he found to be uncertain or untrue. What was left was a single absolute, "I". He had found himself, the truth, but sadly could not maintain it, slowly allowing the uncertainties back into his mind again. If I remember correctly he started with God. Oops! Descartes found the truth, himself, and lost it again.

His process was a great help in finding me. Just me. Everything! Einstein believed as well that simplification or reductionism was the Way to the equation that unites all things. Sadly he came close to truth with his simple equation e = mc2 then like Descartes before him, began to compound his equation again. So much so that he hired mathematicians in the end to help him struggle through. It was Maxwell and his belief in the speed of light that turned him the wrong way. The solution he searched for will change the world someday.

Truth shall set us free.

As for understanding my other comments above, the B poem was a response to "Dasien" or being, that's all.

And the simple thought only in response to John's "Deep thought".

The solution to everything is much more simple than thought!!

=

Guest

Wednesday, July 8, 2015 -- 5:00 PM

I've never been able to getI've never been able to get far into Heidegger either, but two elements of his thought have always intrigued me. Dasein is embedded, a point John makes. But this embedding happens both "outside" and "inside" but there's not necessarily a hard-and-fast distinction between the two spaces. Specifically Dasein is aware of its own demise, which from a naturalistic standpoint flops over both. A friend of mine once argued that Heidegger thought it was the awareness of its own demise that gave Dasein a perception of time. I haven't read enough Heidegger to know whether that's textually true, but it introduces an interesting internal emotional color to Dasein's information processing that I don't think Professor Dretske got into.

Second, there's a bunch of ways in which the notion of Dasein makes Peirce's pragmatism and theory of the practice of science a lot easier to understand. Peirce's formulation of "theorization" makes use of this notion of something along the lines of an irritation that causes the thinker to do something. If we look at Peirce as thinking of the thinker as a Dasein reacting to the medium in which its embodied - which in Peirce's case also allows us to view not just homo sapiens as theorizers, but any of the more complex mammals - we can start to see some big-picture consistency between the two accounts.

MJA

Thursday, July 9, 2015 -- 5:00 PM

Equal Gary is the unifiedEqual Gary is the unified field equation Einstein was searching for.

When all is equal all is One.

Truth is =

Gary M Washburn

Sunday, July 12, 2015 -- 5:00 PM

Mr. Grover,Mr. Grover,

Heidegger makes a very stark distinction between being (dasein) that suffers death and those that merely suffer 'demise'. 'Demise' is defined as inauthentic, or incapable of anticipating its end in the sense of its being an issue for it as the focus of its interests and concerns. 'Dasein' doesn't just strive to stay alive, it knows it must die and so resolves in some way to bring meaning to what time it does have in this life. Heidegger gives us many passages on the subject of in-authenticity. It is called irresolute and therefore so inept in its concern for its own being that it might as well be an animal that only suffers its demise, with no edifice of meaning created that defines its time as a special epoch of being. What this means for the philosophical ramifications of the fascination with the question of the meaning of being is a long and arduous road that I would not want to step into unless an earnest interest is clearly expressed (and not merely stated!). I have taken that road so long that I have penetrated areas that were only on the horizon for Heidegger, and would find it as difficult to introduce to a tyro as to refer it to a long elapsed interest in things Heidegger.

Michael,

Do you suppose Maxwell and Einstein were contemporaries? It was the Lorentz transformations, based on the Michelson-Morley experiment, that convinced Einstein, and all reasonable physicists, that the speed of light is a constant. Maxwell was a pre-relativity physicist. You keep making cryptically 'learned' references that begin to look more like cribbing. The 'insight' of Descartes has been thoroughly discredited. Self-certitude is most vagabond basis for a philosophical system. If you would understand the 'cogito sunt' I suggest you do some thinking. The one you will go one about has no oneness to it. Either it is a unity that cannot count the multiplicity of units as any oneness it is, or it is a multiplicity counted only with no unifying oneness to it. Either way, your certitude in it is vapid. '=' simply does not mean what you say it does. You're just flat wrong about that. Logic 101 would knock that nonsense out of you. Dogma has a certain advantage, I understand that. It simply reasserts the same thing in the hopes that, eventually, all adversaries will be so forced to use your own terms that you can thereby simply and literally define them, by fiat of the terminology, in agreement with you. Have you ever seen a person 'saved'? It's quite a process. A person is surrounded by the community under the direction of an imperious preacher, and bullied into 'accepting the faith'. It's quite exactly like watching someone being tortured into confessing being a witch or a heretic. And what is really appalling is how the congregation regards this crime and inhumanity as a holy event. Michael, you're getting no hallelujah moment from me, and hopefully not from anyone else on this site. Meanwhile, I'm starting to feel like your posts are part of a Turing test, a badly programmed one.

Harold G. Neuman

Saturday, April 21, 2018 -- 1:17 PM

I read Being and Time. It wasI read Being and Time. It was interesting. But over-rated.

Harold G. Neuman

Wednesday, May 9, 2018 -- 12:38 PM

I do not see how anyone wouldI do not see how anyone would characterize Heidegger as the greatest philosopher of the twentieth century. If Being and Time is considered his finest work, then, like John Perry, a priori Kevin Gin, I found Heidegger's writing incomprehensible gibberish. Now, I suppose there are those who assert that they know what he was talking about. If they truly do, then one might see how they could rate him so highly. I cannot do so, because there are living twentieth century philosophers who, in my opinion, vastly outpace the thinking skills of Martin. As do several who have met their 'demise'. There is quite a difference in writing obscurantist prose with profound-sounding catch phrases and actually and methodically, presenting theory with studied arguments and evidence to back it up. It is one matter to write philosophy that classically trained philosophers can understand. It is something else when the writing is so convoluted and tautistic that one cannot help but think the writer was winging a fantasy, known and knowable only to himself. One commentator wrote that Ken Wilber was his/her favorite for best of the twentieth century (and this one as well.). I read His earlier work and concur that it was well done. My first choice, though, would have to be John Searle: his clear-headedness and facility with linguistics makes his work enjoyable. And even someone green to philosophy can make sense of it. That I discovered his work late in life does not diminish its enlightening quality.