Why Propaganda Matters

May 31, 2015Governments and other political institutions employ propaganda to sway public opinion, instill ideas, and exert a degree of control over people.

The notion of ideology is very important in political thought, as well as in everyday discourse. But even though scholars have produced mountains of erudite writing on the topic, there’s disagreement about exactly what ideology is and how, if at all, we can square the various notions of ideology with one another.

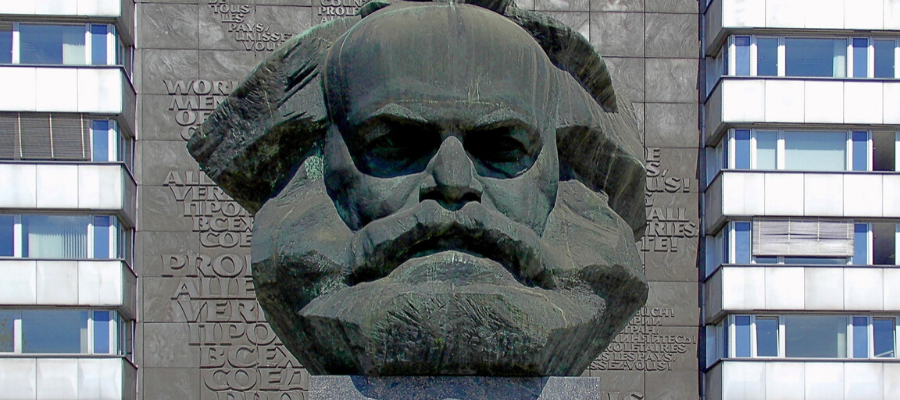

Most current notions of ideology grew out of the 19th century writings of Karl Marx. Marx’s main discussion of it is in The German Ideology, an early work that he co-authored with his friend and benefactor Friedrich Engels. Marx and Engels argue that economic forces drive social life. It’s the economic facts on the ground, and the class structure arising from them, that are responsible for the beliefs, values, and assumptions that are prevalent in any society. In their day (as in ours) most people took it for granted that it’s our beliefs and values that shape economic structures, rather than vice versa. But Marx and Engels turned the commonplace view on its head. They argued that people who believe that ideas have priority over the material conditions of life are enmeshed in the web of ideology.

They illustrate their point with an intriguing analogy. “If in all ideology men and their circumstances appear upside-down as in a camera obscura, this phenomenon arises just as much from their historical life-process as the inversion of objects on the retina does from their physical life-process”. A camera obscura is a box (or sometimes a whole room) with a small hole in one of its sides. When light shines through the hole, it projects an upside-down image of the outside world on the opposite interior wall of the box, just like the way that light passing through the pupil of the eye projects an inverted image on the retina. Their point is that ideology presents us with an upside-down picture of the social world—a deformed representation which, if we are not careful, we are likely to mistake for reality.

There’s more to extract from the metaphor. The camera obscura wasn’t designed to produce an upside-down image. That it does so is a consequence of the laws of optics. The human eye wasn’t designed (in this case, by evolution) for producing upside-down images either (our brains have to turn the image right-side-up). Bearing this in mind, Marx and Engels’ analogies suggest that ideology doesn’t have the purpose of generating a distorted picture of the social world. The inversion is just a consequence of the “historical life-process”—the laws that govern the development of social systems.

I’ll use an example to illustrate this point. White supremacism, the ideological belief that white people are intrinsically superior to people of color, got going during the 17th and 18th centuries alongside the development and expansion of transatlantic slavery. It’s tempting to imagine think that Europeans enslaved Africans because they regarded them as inferior, but Marx and Engels would say that this explanation puts the cart before the horse. The truth, they would say, is that white supremacism was a consequence of slavery rather than its cause. Europeans didn’t enslave Africans because they believed them to be inferior: they believed them to be inferior because they enslaved them. And Europeans didn’t intentionally craft the ideology to suit their purposes; it emerged as a result of the rise of a capitalist economy that allowed planters to rake in huge profits using slave labor.

The picture of ideology that I’ve just presented sits uncomfortably beside a different strand of Marxist thinking—one that states that ideologies are designed to legitimate the status of ruling elites. Terry Eagleton rightly notes in his book Ideology: An Introduction that, “This is probably the single most widely accepted definition of ideology” and he goes on to list six “strategies” by means of which they are implemented.

A dominant power may legitimate itself by promoting beliefs and values congenial to it; naturalizing and universalizing such beliefs so as to render them self-evident and apparently inevitable; denigrating ideas which might challenge it; excluding rival forms of thought, perhaps by some unspoken but systematic logic; and obscuring social reality in ways convenient to itself.

Reading this description, it’s easy to imagine that the 1% deliberately concoct and promote ideologies to keep the 99% in line. But this way of looking at things bumps up against the fact that the purveyors of ideology are addicted to their own Kool-Aid. Far from being cynical manipulators, they believe, often zealously, in the falsehoods that they dispense. Of course, it would be breathtakingly naive to say that the Powers That Be never feed disinformation to the public. Of course they do. But this is propaganda, not ideology. The beneficiaries of the transatlantic slave trade didn’t (for the most part) wittingly fabricate lies about white superiority in order to feather their own nests. They really did believe that white people are intrinsically superior to people of color.

The two descriptions of ideology that I’ve presented seem irreconcilable. One takes ideology to be the offspring of impersonal economic forces, and the other claims that it has the purpose of maintaining the power of dominant elites. Each view makes sense, but it’s hard to see how they can both be true.

I think that there’s a solution to this puzzle—a way to meld the two accounts into a seamless whole. It’s one that comes, oddly enough, from the philosophy of biology. Let me explain….

When we’re trying to understand the natural world, the principle that parts of organisms have purposes—that there’s something that they’re for—seems both obvious and indispensable. Eyes are for seeing, wings are for flying, teeth are for chewing, and so on. But how can account for the purposes of natural things? Clearly, things like eyes, wings, and teeth aren’t like can-openers, which get their purpose from the intentions of their designers (thanks to Darwin, God exited the explanatory arena a long time ago).

Philosophers have tried to solve this problem ever since the time of Aristotle, but they’ve not been successful until recently. A philosopher named Ruth Millikan seems to have finally figured it out, with the help of the theory of evolution. Her explanation goes like this. For a natural thing to have a purpose it’s got to be part of a lineage—that is, it’s got to be a reproduction (or a reproduction of a reproduction) of some prior thing, and there’s got to be something about what the ancestors of that thing did that caused them to be reproduced. The purpose of any natural thing is whatever its ancestors did that caused them to be reproduced.

As is often the case with philosophical theories, this description makes the thesis sound a lot more complicated than it really is. Here’s the idea. Hearts pump blood. They also make a pitter-patter sound. It’s a no-brainer that the purpose of hearts is to pump blood rather than make a pitter-patter sound. That’s because pumping blood, rather than making a pitter-patter sound, accounts for why hearts were reproduced down the generations.

The utility of this theory far outstrips biology. Anything can have a purpose if it’s part of a chain of reproductions that get copied because of their effects. It can be used to explain the purposes of words, social conventions, learned behaviors and….ideologies. Ideological beliefs are members of lineages. And they’re reproduced, again and again, because of their effects, and these effects are their purpose.

Looking at things from this perspective banishes the appearance of contradiction. It allows us to understand how ideologies can be the upshot of non-intentional social processes and yet also have purposes. Let’s consider white supremacism one last time to see if this analysis pans out. Slavery was big business. Europeans accumulated enormous fortunes by creating and sustaining what was, in the words of the historian David Brion Davis, “the world’s first system of multinational production for what emerged as a mass market – a market for slave-produced sugar, tobacco, coffee, chocolate, dye-stuffs, rice, hemp, and cotton”.

It is easy to underestimate its gargantuan scale. “By 1820 more than 10.1 million slaves had departed from Africa to the New World, as opposed to only 2.6 million whites […].Thus by 1820 African slaves constituted almost 80 percent of the enormous population that had sailed toward the Americas, and from 1760 to 1820 this emigrating flow included 8.4 African slaves for every European”. The host of planters, merchants, importers, manufacturers, shipbuilders, insurers, and others who reaped rewards from the trade in human flesh were not, for the most part, sociopaths. They were people like you and I who had normal moral sensibilities and they lived in an era where ideas about liberty, autonomy, and universal human rights were gaining momentum. If they people had granted that Africans were their moral equals, the atrocity of slavery would have been more difficult to countenance. It’s easy to see why white supremacism got traction in these circumstances. It proliferated like a virus, reproducing again and again, because of the advantages that it allowed believers to accrue. And it’s these advantages that fixed its collective purpose, transforming it from a mere idea into a full-blown ideology.

In conclusion, it turns out that the two views of ideology, which at first seemed to be at odds with one another, are entirely compatible. Ideologies arise from purposeless economic forces and they have the purpose of legitimating dominance. They’re self-serving representations of the political landscape and those who endorse them are committed to their truth.

It’s excruciatingly difficult for those of us who are ideologically entangled (including virtually every fan of Philosophy Talk and every reader of this blog) to free ourselves enough to see through the distorted representations to the disturbing social reality beyond. But if anything has the power to assist us in this liberatory task, it’s good, clear, politically engaged philosophy.

Comments (2)

Gary M Washburn

Sunday, June 7, 2015 -- 5:00 PM

The paradox is quite simple.The paradox is quite simple. How do you explain the emergence of a prejudice? Without undermining it, you can't. Therefore, in order to sustain it, you mustn't explain it or permit investigation of it.

If, that is, the 'idea' is an enforceable perspective and its 'logos' or 'logic' is its explicable emergence and sustaining or enforcing rationale. Hence 'ideo-logy'.

Gary M Washburn

Monday, June 8, 2015 -- 5:00 PM

The greatest effortThe greatest effort discipline and rigor we can bring to reasoning is what effects our changing our minds. The can be no resolution to sustain a view that can claim anything like the effort incumbent upon changing it. Not only that, but if we enjoin in such extreme discipline, if we share in a setting in which icons of culture and ethos ot faith are proved inadequate to their premise or in their promise, if we share recognition of this iconoclasm, we recognize too that, however small as sense in which that icon is defamed or profaned, that our sharing that recognition introduces to us that whole most extensive rigor reason can be each alone. The secret is dispelled. That is, an inadequate reaonsing that sustains our prejudices cannot be fully revealed to and for each other, cannot lose its inherent secrecy and isolation such limited reason is between us. But where the completed rigor of a changed icon of ethos becomes recognized amongst us, we are not necessarily instantly known to each other, but we are known the most extensive personal reasoning is unhidden in that moment. And if that moment is not as alone as that uncompleted reasoning a sustained perspective is, then what grows of it can only be all the more unhidden. We do come to know each other as completely as that reasoning is completed in the changed mind. Ideology, of course, is the process, by whatever means, that averts the moment. But only what has a secreted motive to obviate our knowing each other can sustain that process. And, no, it is not just a left-wing myth that it works this way. Plug Hegeliansim into that and watch where it leads.