Gandhi as a Philosopher

Nov 16, 2008Gandhi is famous as the leader of the movement for Indian independence, which he based on his philosophy of non-violence, an important influence on Martin Luther King Jr.

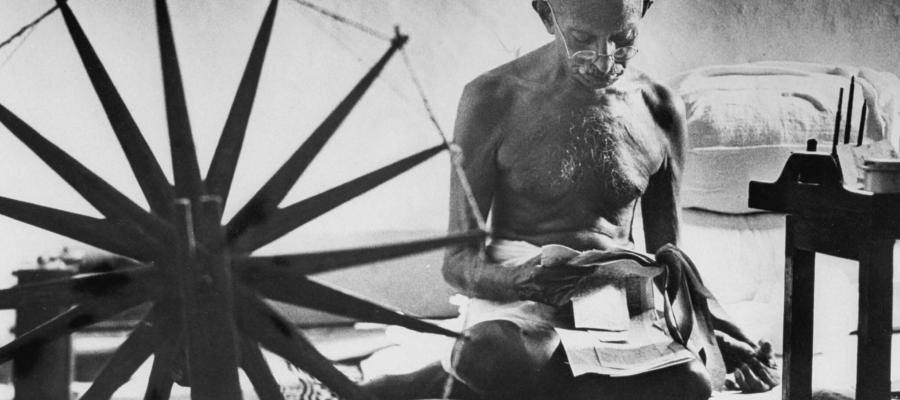

Our topic this week is Gandhi as philosopher. That would be Mahatma Gandhi, the great spiritual and political leader, father of the Indian Independence movement. The man who preached and practiced non-violence, and inspired millions around the world -- including America's own apostle of non-violence, Martin Luther King. Though one may not typically think of Gandhi as a philosopher, he was, in fact, a profound philosophical thinker. He wasn't an academic philosopher like John and me, but he wrote a lot that could be called philosophy.

To be sure, academic philosophers would probably find his philosophical writings frustrating at times. But when you realize that Gandhi's spirituality, his approach to politics, and his philosophical outlook are interconnected, then you realize that if you really want to understand the phenomenon that was Gandhi, you have to also understand his philosophical outlook.

And we’re betting that a taste of Gandhi as philosopher and how it might help us better understand Gandhi the spiritual and political leader. Take, for example, Gandhi's views about morality. You might think that the leader of non-violent non-cooperation, as he liked to call it, would be big on moral condemnation of his opponent, and would be constantly claiming the moral high ground. After all, revolutionaries do tend to criticize the old order as morally problematic.

Just as an aside, though, I should point out that one could wonder whether it is completely fair to call Gandhi a revolutionary. He didn't lead an armed rebellion, like most revolutionaries. He and many of his followers were willing to be killed, but they weren't willing to kill. And the term 'revolutionary' does tend to connote the violent, rather than the peaceful overthrow of the old order. So I'm not sure we have a good word for exactly what Gandhi was.

But let’s get back to Gandhi and morality. Most revolutionaries – or whatever exactly Gandhi was – are utterly and inalterably convinced that they have morality wholly on their side. Though Gandhi was a deeply principled man who constantly strove to be on the side of morality, he wasn't big on claiming to know the moral truth. And he actually thought that the ethical condemnation of one's opponent was itself a form of violence. And he rejected all forms of violence.

That can seem a little puzzling. If you have morality on your side, what's so bad about claiming that you do? Isn't that just stating what you believe to be true? But it’s worth making two points in this connection. The first one is about truth. Gandhi had very complicated views about truth. He believed there is such a thing as absolute truth. And he felt he was on a quest to know the absolute truth. But he also thought that that quest for truth was unending and uncertain. Only God actually knows the absolute truth. Gandhi, in fact, took it to be a form of arrogance to claim to have the absolute truth on your side in disputes between humans. We, humans, only know what he called relative truth.

That makes Gandhi a kind of relativist, in a way. One might reasonably suppose, then, that it must have been his relativism that led him to reject moral condemnation as a form of violence. Relativists, after all, promote tolerance of competing points of view and competing moral outlooks. Problem is that Gandhi can't really be called a straight-forward relativist. Relativists tend not to believe in absolute truth -- even as the elusive object of an unending quest. But that’s just what Gandhi did believe. Of course, Gandhi isn't straight-forward absolutist either. At least some absolutists think that they have a firm grip on the absolute truth. And under the illusion, at least as Gandhi would see it, that they alone know the absolute truth, they tend to lord it over those who disagree with them. Gandhi would never pretend to know the absolute truth and would never lord it over anyone.

I'm not sure, but Gandhi's attempt to sort of have it both ways makes things a little complicated. Suppose we follow Gandhi and say that lording it over others, under the illusion that you alone grasp the absolute truth, is a form of violence. Well then, aren’t we criticizing and morally condemning the other? But by Gandhi’s lights, moral condemnation is itself a form of violence. So don’t we have to reject even this moral condemnation? But that, it would seem, doesn’t make any sense. It prevents us from simply stating what we take to be the case -- that one shouldn't lord it over others under the illusion of having sole possession of the absolute truth. But the very rejection of that way of looking at things is built into Gandhi's own way of thinking. So it looks like Gandhi can't really declare hi sown principles, maybe.

Maybe we should turn this around, though, and look at it from the perspective of the opponent, to see what Gandhi is getting act by rejecting righteous moral criticism as a form of violence. I think he pretty clearly thinks that if you constantly criticize your opponent, that the opponent will experience your condemnation as an attack. Perhaps not an attack on his physical person but an attack on, as it were, his spiritual person. And that puts your opponent on the defensive. But if you want to win your opponent over or at least lower his resistance, that’s a bad strategy. Whether it's morally wrong is less clear, but maybe perhaps strategically wrong.

You could, I suppose, think that Gandhi is really carrying this non-violence thing too far. Moral condemnation is an attack only in a metaphorical sense and not literally and truly a form of violence. But Gandhi would insist that violence takes many forms -- not just physical. There's economic violence, cultural violence. For Gandhi, moral condemnation is just another form of violence. And he insisted that all forms of violence are to be resisted. It is certainly true that violence takes many forms and that not all of them involve the infliction of direct physical harm to the body. But I'm still not completely convinced that freedom from violence of any kind would entail freedom from moral condemnation.

I haven't unravelled, by any means, the puzzle of Gandhi. He was clearly a complicated man. And he was a complicated thinker too. It’s not at all obvious that his views really add up to philosophically speaking. But fortunately, for this episode John and I were joined by a man who has thought long and hard about Gandhi: Akeel Bilgrami author of "Gandhi, the Philosopher".

Comments (3)

Guest

Saturday, September 25, 2010 -- 5:00 PM

Gandhi's philosophy was equality and his work wasGandhi's philosophy was equality and his work was simply to equate. And for those still searching for the truth, try it, you'll see.

Truth is much more simple than thought:

Empirically equal or mathematically = is the absolute truth.

=

MJA

Guest

Sunday, September 26, 2010 -- 5:00 PM

Outstanding piece on Gandhi. Thoughtful and thoughOutstanding piece on Gandhi. Thoughtful and thought provoking. I may be all wet here but I believe anyone who is a student or practicioner of political and spiritual matters is, by association, philosophical in his/her outlook. These disciplines are all parts of the consciousness of modern (and even not-so-modern) mankind. I have written a few things on this association myself. They may be found on the Morning Buzz blog referenced by Comrade Ade in his 15 Minute Philosopher blog.

Sincerely, PDV.

Mehr

Friday, March 12, 2021 -- 5:59 AM

Hi. I am a man at 48 yearHi. I am a man at 48 year from Iran. I am interested in the spiritual and moral way to the truth which Mahatma Gandhi advised in his auto-biography. He wrote Ramayana of Tulsidas as devotional literature and Bhagavata as religious fervour. I am new in these literatures; therefore, I need some help. I do neither know how to get them as English publication for first-time readers nor how to read them. I would be very grateful if you give me some advice.