The Limits of Self-Knowledge

Oct 06, 2013Descartes considered the mind to be fully self-transparent; that is, he thought that we need only introspect to know what goes on inside our own minds.

Last month, I described how ideas inspired by the work of the 17th century philosopher René Descartes cast a long shadow over the sciences of the mind. One aspect of his influence concerned beliefs about the relationship between the human mind and the human brain. In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, most scientists of the mind were dualists. They believed that although the brain is a physical organ, the mind is a non-physical thing that’s distinct from it.

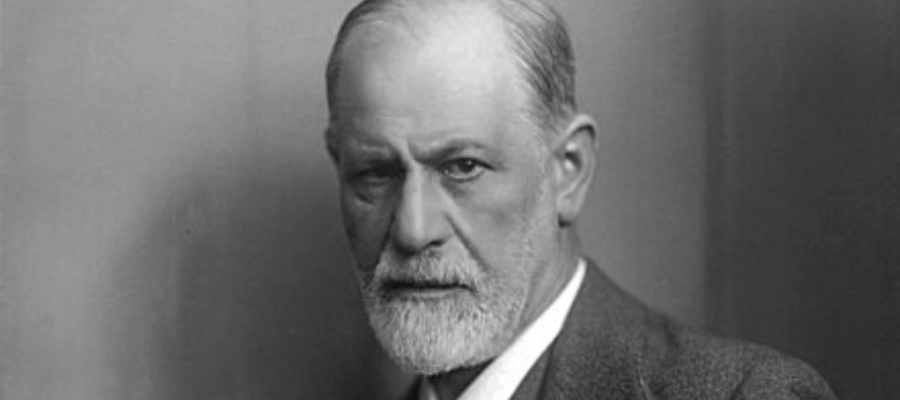

Another aspect of the Cartesian influence had to do with the mind’s relation to itself. Most of Freud’s contemporaries believed that the human mind is automatically aware of its own contents. In a nutshell, they held that the human mind is all conscious.

The notions that the mind is not the brain and that the mind is all conscious are closely connected to each other. Think of it this way: it seems obvious that we don’t have access to the processes going on inside our own brains. For instance, try as you might, you can’t tell me which of your neurons are firing as you read this sentence. But you can easily access the mental state that you’re in while you’re reading it. This might lead you to conclude—just as the 19th century scientists of the mind did—that mental states have got to be distinct from brain states, so mind ≠ brain.

That’s all good and well, but the scientists and philosophers who endorsed the view that mental states are always conscious had to find a way to make sense of observations that didn’t seem to fit into this picture. Some of these came from experiments in hypnosis. A hypnotic subject could be given a post-hypnotic suggestion, say, to jump up and down when the hypnotist snaps his fingers. After coming out of trance, the person—let’s call him Ludwig—starts jumping up and down when the hypnotist snaps his fingers.

Now here’s the most important bit: when Ludwig is asked why he’s jumping up and down he either confabulates—for instance, by saying he that wants to get some exercise—or else he just says something like “I don’t know, I’m just doing it.” But it seems right to say that Ludwig’s behavior was brought about by a mental state of which he, the bearer of that state, was unaware. The dude literally didn’t know what was on his mind.

We don’t have to go to hypnosis to find examples with the same significance. Freud was particularly impressed with the uncanny phenomenon unconscious problem solving. Most people have experienced this sort of thing. You’re struggling unsuccessfully to work out the solution to a problem. Eventually, you set it aside and go to bed. The next morning, you wake up with the answer right there in your head. In fact, you don’t even have to go to sleep for this to happen. Sometimes all you’ve got to do is shelve a problem and then the solution pops into your head, seemingly out of the blue.

You weren’t aware of working on the problem while you were asleep—at least consciously. During the night you spent some of your time in deep dreamless sleep, when your consciousness was completely turned off, and the rest of your time having weird and irrelevant dreams. But solving the problem clearly required cognitive work, so all this cognitive processing must have been going on unconsciously.

There are loads of examples of this sort of thing in the history of science. I’ll share just one. The great German mathematician Carl Friedrich Gauss had been working on a proof for two years, without success, when suddenly the solution popped into his head. He wrote in a letter, “Finally, two days ago, I succeeded not on account of my painful efforts, but by the grace of God. Like a sudden flash of lightning, the riddle happened to be solved.” The next sentence of his letter is important: “I myself cannot say what was the concluding thread which connected what I previously knew with what made my success possible.” In other words, Gauss didn’t have a clue about how he worked out the proof.

Facts about posthypnotic suggestion and unconscious problem-solving are hard to square with the claim that the mind is all conscious. You’d think that the obvious conclusion to draw from examples like these is that mental processes can occur unconsciously. That’s an easy move to make in a post-Freudian world. But people were not living in a post-Freudian world back then. For most of them, the idea that mental states are conscious (and that conscious states are mental) was axiomatic. It was treated as what philosophers call an analytic truth—a statement that’s true by definition, like “one plus one equals two” or “triangles have three sides.” To deny such claims saddles you with a contradiction. The definition of a triangle states that it’s a three-sided geometrical figure, so saying that a triangle doesn’t have three sides boils down to saying that something that’s a triangle isn’t a triangle! That Freud’s philosophical contemporaries thought that consciousness was part of the very concept of mentality explains why he often complained that philosophers criticized his views by saying that the very idea of unconscious mental activity is self-contradictory.

To fit these awkward facts into the theory that all mental states are conscious states, you’ve got to find some way of denying that unconscious mental activity played a role. There were two options on the table. The first was to argue that the problematic states are unconscious, but not really mental. The second was to argue that they’re mental, but not really unconscious.

Advocates of the first option argued that seemingly unconscious mental states are really just mindless brain states with the power to elicit thoughts and produce behavior. As the great 19th-century neuroscientist Gustav Fechner put it:

Sensations, ideas, have, of course ceased to actually exist in the state of unconsciousness, insofar as we consider them apart from their substructure. Nevertheless, something persists within us, i.e., the psychophysical activity of which they are a function.

This isn’t very plausible. To buy it, you’ve got to swallow the claim that Ludwig’s performance wasn’t caused by anything going on in his mind. But Ludwig’s strange behavior is inexplicable unless we accept that the hypnotist implanted the idea of jumping up and down in his head, and that it was this idea is what made him jump. Ideas are mental.

The example of sleeping on a problem is even harder to accommodate. Problem solving is mental work, so a person who unconsciously solves a problem must be doing unconscious mental work. That conclusion seems avoidable.

Advocates of the second option claimed that a single consciousness can be split into two or more independent consciousnesses, and that that’s what explains the Ludwig and Gauss cases. As the philosopher and psychologist William James put the idea in his 1890 book The Principles of Psychology, the “Total possible consciousness may be split into parts which coexist but mutually ignore each other, and share the objects of knowledge between them.” The term “subconscious” was specifically associated with this thesis, which is why Freud avoided it and used the term “unconscious” instead.

If this is right, then it wasn’t Ludwig’s main consciousness that had the intention of jumping—it was a split-off portion of his consciousness—a sort of mini-Ludwig stationed inside his mind. And the same sort of explanation goes for Gauss’ mathematical deductions.

This way of making sense of the examples is pretty weird. One reason it’s weird is that the divided consciousness approach pictures consciousness as something that can be divided into pieces without losing its integrity. It pictures consciousness as something that’s simple and homogeneous—like ice cream. You can spoon ice cream out of a tub into three bowls without it ceasing to be ice cream, but you can’t divide complex systems up like this without wrecking them. If I chop my washing machine into three parts, I don’t get three small washing machines. I get three pieces of junk.

So, to accept the sub-consciousness theory, it looks like you’ve also got to embrace the view that the mind is more like a tub of ice cream than it’s like a washing machine. The idea that the mind is simple and homogeneous rather than complex and organized doesn’t make much sense when you really think about it. How could something like that figure out a complicated mathematical proof? It makes a lot more sense to think of the mind as highly complex and exquisitely organized—but then, if you also claim that the mind can be divided, you end up with the washing machine problem.

Early in his career, Freud accepted the mainstream view, and wavered between the two positions I’ve just described. But before long he trashed both of them. He rejected the split consciousness theory because (as he put it in a 1915 paper) it’s odd-going-on-incoherent to suppose that there could be “a consciousness of which its own possessor knows nothing” and baulked at the fact that it licenses “the existence not only of a second consciousness, but of a third, fourth, perhaps of an unlimited number of states of consciousness, all unknown to us and to one another.”

In my next essay on Freud’s philosophy, I’ll unpack Freud’s rejection of Cartesianism, focusing on his argument not only that there are truly unconscious, truly mental events, but also that all mental events are brain events—that minds don’t interact with brains because minds are brains.

Comments (2)

Harold G. Neuman

Wednesday, February 6, 2019 -- 11:17 AM

On this topic, I once made anOn this topic, I once made an observation on unconsciousness, based generally on what a well-known philosopher had said about the terminologies of philosophy and related disciplines of mind, and how those evolve (or emerge) over time and experience. The man I mention will remain nameless, because his views (if he is still among us) have always been curmudgeonly, if not downright recalcitrant. Anyway, he allowed as how he could not buy 'unconscious' because unconsciousness, as a conceptual notion, means a lack of wakefulness, inability to think, act, or respond to external stimuli. So, in his opinion, those who would examine a human 'unconscious', or name it as such, are not identifying a mental state with the term, rather, they are describing something in a paradoxical way---which does not appear to get anywhere near what they are trying to identify. I don't know if he ever changed his mind about this assessment, or even tried to better isolate what everyone has been trying to talk about. Certainly, there must be some way to do this; some word which captures a true meaning. If sleep states are actually periods of brain activity (they appear to be), and brain activity is, by broad definition, thought, then perhaps we could call the unconscious something different. SOMNOLENCE might do, if we re-define what THAT is. Linguistics fails us, until we figure out how to wrestle it into submission.

Aadeewat

Tuesday, February 12, 2019 -- 8:52 PM

Having read your recent postHaving read your recent post of 4 Feb 2019 has brought forth a recurring idea that if you don't mind I would like to suppose a different reality/mind view of my own. Or at least I believe it to be. :)

As we have confirmed with ever increasing accuracy Einstein's Explanation of the macro universe. Yet at the same time we are in a much younger phase of the science of dealing with the sub micro or quantum state of the universe.

I believe that many of the mind/brain being questions can be answered by what I like to call the quantum reality state of being or quantum life. Now bear with me I don't just mean sticking "quantum" in front of something and saying it is all a mystery.

So quantum life is the idea that in the quantum controlling reality of our existence and universe a part of a person's fate are indeed cast. Cast in the generation of a quantum value represented by the maximum number of bit/life solutions a being has... a quantum value which represents all the possible existences that being can have. This number is finite. While the multiverse may have infinite outcomes, you don't exist and can not exist in many if not most of the outcomes.

The value is also influenced by environment and real world, as in the Einstein reality, while unavoidably influenced by quantum data and nature of the universe as being revealed to us. Immediately upon being generated the possibilities begin winking out, the quantum clock begins ticking in one respect.But the thing that we have come to call reality is in actuality the merged realities of all surviving bit/lives. However due to the quantum nature of our universe in keeping with the macro time/space reality EACH QUANTUM BEING EXPERIENCES THE MAXIMUM LIFE IN TIME OF THEIR PERCEIVED REALITY. A somewhat blunt way of putting this is it is always the other you who dies.In all the ways and in all the places that your individual bit/lives continue then so do you and your perception of reality as a single coherent state. And this reality or perception thereof ends always on the last longest surviving bit/life. Ironically also the recipient of the last and highest final "wisdom" return from all the existences including the non-surviving of the quantum universe. With each bit/life ended the remaining quantum of continuing existences coalesce with loss of energy and states and no apparent reality view change for the quantum being. To continue in their conceptualized universe until the maximum quantum generated number is ended.

The exerting of life force vitality is indeed a macro universal thing, yet strangely is also a result of quantum interaction. For instance a younger macro quantum being also enjoys the quantum feedback of a high bit life quantum number and multiplier. While longevity can be ascribed to environmental factors it can also be accounted for by having a higher bit life number that definitely results in a longer perceived reality for the quantum being to enjoy. Just has been realized or is being realized with dna in the Einstein universe indicates their really maybe no practical limit to biological longevity -there also does not seem to be a limit to the quantum life bit generating value, operational positive amplification between both realities through the mirror of time.

Now if you don't mind I would like to try application to problems you discussed in above referenced post.

For instance the human mind and the human brain. If I may quote yourself"

Another aspect of the Cartesian influence had to do with the mind’s relation to itself. Most of Freud’s contemporaries believed that the human mind is automatically aware of its own contents. In a nutshell, they held that the human mind is all conscious."

And from a quantum being is in fact all consciousness. Our reality is a conglomeration but unified into a single field of view we call reality. Even the hypnotized client is still receiving data from unsuccessful hypnosis tries. The reason the person fights the single life/bit outcome so vociferously is because it really does not conform to their perception of reality as generated by the combined bit/life outcomes. Forcing the quantum being to try to incorporate/acknowledge a single bit/life result causes the quantum being to rebel against a reality they are really not experiencing.

"That’s all good and well, but the scientists and philosophers who endorsed the view that mental states are always conscious had to find a way to make sense of observations that didn’t seem to fit into this picture."

The man who awakens from a sleep or years of work is still receiving data from the quantum realm and their combined bit lives. Just as in the bit/life dedications through multiple bit/lives to the violin. Somewhere on that bit/life tree, so to speak, you are in fact concentrating on each note. But benefiting from the then combined resource. Or any single life/bit success at problem solving is immediately shared with the combined quantum being. This then appears to be sudden success on a insurmountable problem to the quantum being.

"You weren’t aware of working on the problem while you were asleep—at least consciously. During the night you spent some of your time in deep dreamless sleep, when your consciousness was completely turned off, and the rest of your time having weird and irrelevant dreams. But solving the problem clearly required cognitive work, so all this cognitive processing must have been going on unconsciously." I can do you one better- I initially had this idea immediately upon awakening from a medical induced coma.

I think you see where I'm going. Somewhere on that bit/life tree you were not asleep or the combined resolution is the result of quantum derived bit/life information of the many more the one bit/life solution. From the quantum being's point of view it would in fact appear as a sudden revelation.

"Advocates of the second option claimed that a single consciousness can be split into two or more independent consciousnesses, and that that’s what explains the Ludwig and Gauss cases. As the philosopher and psychologist William James put the idea in his 1890 book The Principles of Psychology, the “Total possible consciousness may be split into parts which coexist but mutually ignore each other, and share the objects of knowledge between them.” The term “subconscious” was specifically associated with this thesis, which is why Freud avoided it and used the term “unconscious” instead."

Barking at the moon trying to make reality fit a point of view in both cases. Perhaps subconscious and conscious as in quantum consciousness is not the result of one or two states but the combined...well you get the idea.

Of course this does not include brain function even as in automatic brain function. That is a single bit/life result that does not have a function in the quantum being. Other then as a bit/life result.

Let me step out even farther on a limb that is no doubt creaking. I want to pull from the past and discuss a near human but single bit/life conscious being. Homo erectus survived for what? 1 to 1.5 million years. You can find their handaxes all over the old world. Funny thing is though, those hand axes never changed much in a million years. Not much more than a baboon with a stick. Humanity is a quantum being, (apparently not much more than 150 thousand years old and look what we have done) and is simply not capable of NOT changing in a hundred or thousand years.

A case for and against dogs. The difference between a being and a quantum being is the individual reality contained with the being and the combined reality of quantum beings. When a deer is killed by a lion it experiences every bit of the pain and horror of the situation but just like a man on an island. That is existence for good and bad. The quantum being is constantly being reinforced with information being perceived on all bit/lives..failures included. This meshed reality view experienced as one also allow the quantum being to experience time and reality differently. First the idea that the pain can end, (and in fact with the quantum being always ends), does effect perception of reality until the last bit/life is extinguished.

Enough to make the point I assume and also a drop in the bucket compared to what I feel I could drone on about. So I won't.

I hoped you enjoyed my idea and maybe some food for thought?

Thank-you for your time and be assured my day job gives me little room for waxing on philosophy and consciousness states as well as working on style and quality writing, so would appreciate your understanding and also therefore would relish any feedback you might have.

Most sincerely

Aadeewat