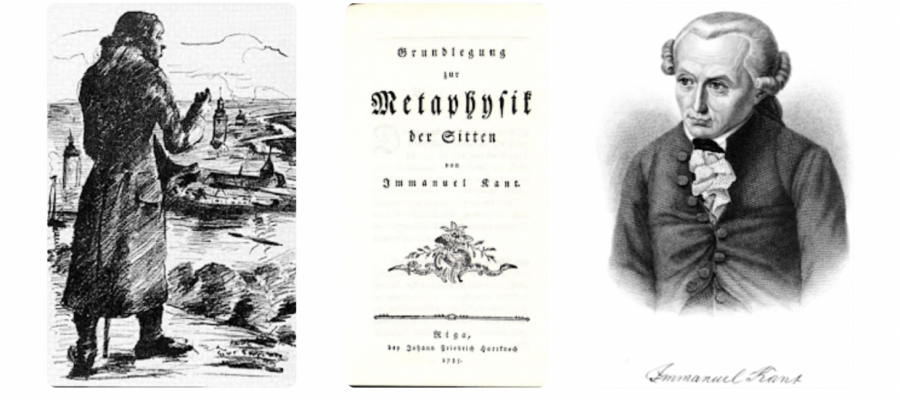

What Would Kant Do?

Apr 17, 2022German idealist and moral philosopher Immanuel Kant is probably best known for his "Categorical Imperative," which says that you should...

Can you reason your way into being a good person? Or are your feelings a better guide for doing the right thing? Should morality be the same for everybody? This week we’re thinking about German enlightenment philosopher Immanuel Kant and his view of a universal morality based on reason.

Kant accepted that feelings are important alongside reason—that it’s good to cultivate cheerfulness, and bad to laugh at people in a mean-spirited way. But he thought that our emotions could easily lead us astray, and that only reason can be the final arbiter. Feelings like empathy can motivate you to do good, but they can also lead you astray: what if your empathy for a thief motivates you to help them break into your neighbor’s house and steal all your neighbor’s things?

And you should be willing to do the right thing even when you don’t have warm, fuzzy feelings: it would be wrong to break a promise to visit your friend in the hospital just because you didn’t happen to feel like going.

You might object: can’t your reason get it wrong and your emotions get right? Think of Mark Twain’s protagonist Huck in his novel Huckleberry Finn. Huck’s friend Jim is a runaway slave, and Huck has to decide whether to turn him into the authorities. Huck’s brain says that the answer is yes: it’s his duty to obey the law and return runaway slaves to their owners. But his heart says no. In this case, Huck’s brain is clearly wrong.

Kant could reply that Huck’s brain is wrong because he’s failed to reason properly: reason would tell him that slavery is wrong, because it’s using another person as a means to an end. (Unfortunately, Kant himself didn’t have a great track record on opposing slavery, and he wrote a lot of explicitly sexist and racist things. Contemporary Kantians, or followers of Kant’s philosophy, would say that slavery is contrary to reason, and that Kant just did a bad job of applying his own ideas.)

Not only does Kant think that reason is our best guide to morality, he also thinks it gives us a categorical imperative. That’s an impressive piece of jargon, but it basically means that reason commands us to do certain things (that’s the imperative part), and that unlike other commands, there’s no way to exempt yourself (that’s the categorical part). Etiquette tells you that if you want to set a formal table, you should place the salad fork to the left of the dinner fork—that’s an imperative of etiquette. But if you don’t want to set a formal table, then you have no reason to follow that command—it’s not a categorical imperative. Morality tells you not to murder people—that’s also an imperative. And unlike in the etiquette case, you can't get out of that just by not caring about morality—it's a categorical imperative.

But what does the categorical imperative actually say? What does reason tell you to do? For Kant, it boils down to one command: you should never treat anyone as a mere means to an end. This means that you can’t hurt or manipulate others to get what you want; you have to take their feelings into account. That’s why it’s wrong to lie to others to get what you want; it’s a way of using them.

Kant has some other ways of phrasing the same command. (It’s not clear to scholars that they really amount to the same thing, but Kant insists that they do.) Another way of understanding the categorical imperative, he suggests, is to consider your reason for acting, and ask yourself if it would be a good reason for everyone to live by. For example, suppose you’re wondering whether you should lie to impress someone. You should ask yourself: what if everyone lied when they were trying to impress someone? If that happened, we wouldn’t be able to trust each other, so your attempt to lie wouldn’t even make sense: no one would believe you. Since you can’t possibly will yourself to live in a world where everybody lies to impress people, says Kant, reason (and therefore morality) tells you not to lie to impress people.

Applying Kant’s theory is tricky. Kant had a lot to say about a range of applied topics, from lying (always wrong, even if you’re trying to save someone else’s life) to suicide (also always wrong) to friendship (a complicated balance of intimacy and respect) to what to do at dinner parties (best to avoid competitive games and mean-spirited gossip). Contemporary philosophers have applied Kant’s ideas about ethics to a wide range of topics that he didn’t address, from feminism to universal health care.

I still have some doubts about Kant’s way of doing things. Does his distinction between reason and emotion really hold up to scrutiny? If he had trouble applying his own theory, is it really a useful moral guide? Should I even be looking for universal principles to guide my actions, rather than rules of thumb that work well enough in my cultural context?

On this week’s show, Josh and I welcome back ethicist Karen Stohr, author of a new book, Choosing Freedom: A Kantian Guide to Life. I’m excited to hear her answers to some of my big questions, and learn what Kant’s philosophy has to tell us about the moral issues of today.

Comments (10)

Tim Smith

Sunday, April 24, 2022 -- 10:13 PM

A friend and I were drivingA friend and I were driving thru California and Oregon the last couple days. We used Google maps. I did the driving. She helped interpret directions. I am of the age where I like to think about directions still, she just takes them. She is more a Wazer, another Google app that awazes me.

Four times we came upon speed traps, that had me pulling on my parking brake to avoid flashing my brake lights in the sights of the radar gun.

My friend calmly added the speed trap to Google maps.

I asked her why, and she said to help others. We had a little back and forth upon which time we decided that it really didn't help others. We thought it might save us some money in the future, but probably wouldn't save my parking brake any wear.

What would Kant do with Google maps? Would he add the speed trap alert for others? Would he mute alerts? If everyone placed speed trap alerts, traffic cops would be out of business. Would that be considered using people as a means?

The more I thought about this the more confused I got.

dpatis

Wednesday, May 11, 2022 -- 6:19 PM

Putting a speed trap alert onPutting a speed trap alert on google not only helps the driver avoid a ticket but also possibly helps that driver slow down to a safer speed. That is especially helpful when the road is not safe at a high rate of speed. I spoke to a state police officer who said it does not bother him if someone flashes their lights to oncoming traffic to alert them to his presence because the whole idea of him being there is to bring the speeds down to the safer level. Reason will tell you the road is not a racetrack and other people on the road deserve a safe environment. Again, your friend is helping keep the road safe by putting out alerts.

Tim Smith

Wednesday, May 11, 2022 -- 9:31 PM

That isn't how our exchangeThat isn't how our exchange went.

Drivers who speed excessively are keen to avoid speed traps, and excessive speed causes exponentially more crashes and more severe injuries. Reason will tell you not to abet extreme speeders who are the targets of police speed traps for the most part (only .02% of tickets are issued to marginal speeders - https://www.roadandtrack.com/car-culture/a12042701/who-gets-speeding-tic....)

It would be poetic justice to alert a driver who kills your friend 10 miles further on with their recklessness when they could have been served justice earlier had you not warned them.

Not all speed is the same. Very few people go the speed limit on the expressways, in any case. The mix of trucks, cars, and terrain invites a certain level of excessive speed. The hive of highway design guarantees prey for speed traps financed by their citation revenue stream and, of course, their good intentions. Kant would agree with you if all speeders were the same, and they aren't. Setting the google alert uses people as a means to speed up and cause other havoc against their interests. It's never straight up and down, says Devo.

Harold G. Neuman

Friday, April 29, 2022 -- 7:23 AM

Not sure why, but it seemsNot sure why, but it seems (feels like?)to me reason and feelings are aways away from each other. Reasoning implies a process of consideration and evaluation. It is, in an other word, diagnostic. One might have a feeling about what is amiss when the car won't start. The rule of thumb for auto mechanics was the engine had to get fuel and spark. If both were present, the engine should run. There were other contingencies, however. A potato, or other obstruction fouling the exhaust pipe. Feelings may find the problem. Reason (a good mechanic) has a better chance. And, of course, there is no morality, as such, in any of this. I did that on purpose. Neither reason nor feelings, in themselves, signify or define morality. Fact is, that can change with changing times and emphasis. There was probably some point in human history when the mess in Ukraine would not have been tolerated. However, 'circumstances shift as contingencies surface'. Seems to me.

Tim Smith

Friday, April 29, 2022 -- 8:59 AM

If reason doesn't defineIf reason doesn't define morality, with or without feeling, that pretty much removes Kant to the rubbish bin.

Harold G. Neuman

Friday, April 29, 2022 -- 7:18 PM

Well put. Thanks, Tim.Well put. Thanks, Tim.

Tim Smith

Saturday, April 30, 2022 -- 10:05 AM

Harold,Harold,

There is not much solace for me on this to speak well without offering any path. Compassion and pragmatism don't cut it without some Kantian thought. Specifically, systemic immorality - premised on Mandevilles 'The Fable of the Bees,' or situations where one is genuinely conflicted or ignorant of one's moral compass... all these require a bit of rationality to sort out.

I did read Stohr's book, and it helped. I value asking these questions, even in a totalitarian or warped reality like the one we tread. I don't want to retreat to vacuous good old days thinking, and I agree Kant is not the answer in all or most cases even.

NaviS

Tuesday, May 3, 2022 -- 1:54 PM

Kant's famous quote: “TwoKant's famous quote: “Two things fill the mind with ever new and increasing admiration and awe, the more often and steadily we reflect upon them: the starry heavens above me and the moral law within me,” indicates that the basis for rationality itself is what William James later called the "sentiment of rationality," and therefore it could be argued that Kant was Romantic regarding the Pietistic Christian faith that underlies all this thought....

Harold G. Neuman

Sunday, June 19, 2022 -- 4:11 PM

Am quite confused now.Am quite confused now. Leaving the blog.

Good luck all.

Tim Smith

Sunday, June 19, 2022 -- 8:19 PM

Best to you Harold.Best to you Harold.

Take care.